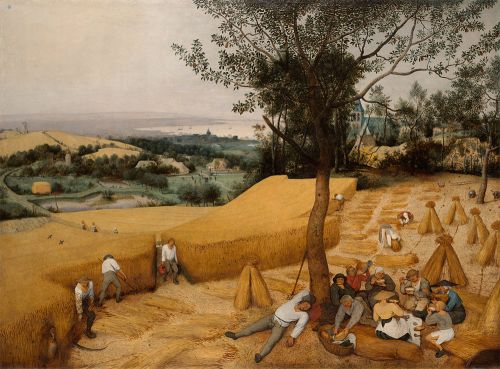

Making breadA Story by SoutieA small adventure into history, botany and baking.Making bread On the island now, days are short, crops are ripening and on sunny days, combine harvesters comb the fields for grain. High above, chevrons of Canada geese squawk a raucous passage to warmer climes and in the grass, crickets celebrate the afternoons in shrill harmony. Such ambrosia invites the mind to wander. And so it was, that during an afternoon walk last week, I hit upon a rather unusual idea. In an uncut corner of a wheat field, from the hedgerow, a startled grouse flew up in a clatter before the dogs. There was of course, barking and feverish scuffling and one presumes, some form of canine embarrassment at being caught off guard. So, while the dogs regained their composure, I stopped awhile and pondered our surroundings, especially the wheat that grew around my feet.  “The harvesters” Pieter Bruegel the elder, 1565 For many years, Bruegel’s print of “The harvesters” had hung in the house and was always a source of fascination, not least of all for its mildly disturbing portrayal of the pre-zipper peasant sprawled below the tree that dominates the painting. What, I thought, would it take to harvest some wheat and transform it into bread like Pieter Bruegel’s peasants had done? Surely, with an education and a zippered fly, I was equally or even better equipped to do so. Although my school days were characterized by a general disregard for academia, rusty recollections of yeast, dough and carbon dioxide sat in disarray on my mental shelves. So too, from religious studies I recalled fragments of how, in their urgency to flee the Philistines, an absence of yeast had made the difference between Matzos and crusty baguettes for the ancient Israelites. In fact, all you really need to make bread is flour, water, yeast and something sugary to feed the yeast. I checked; we had plenty of all the aforementioned in the kitchen, and even a tin of relatively young yeast in the fridge door. Only flour was absent. As if to catalyse this adventure, a mental picture was forming and becoming clearer by the minute; one of melting butter, crusts and the kiss of sweet apricot jam. There are however, more steps than expected between field and fantasy. Even though wheat fields lie just beyond the garden, I knew almost nothing about wheat when this thing began. So when farmer Reid's combine rumbled by me and the embarrassed dogs that afternoon, I held up a hand and beckoned him to stop; if his monster would kindly do so. After a few pleasantries and obligatory remarks on the weather, I explained myself. In essence, what I needed, was “Wheat 101” in five minutes. For starters, was this even the right wheat for baking bread or should I be making pastry or even pasta? Should I be looking to Botticelli for guidance instead of Bruegel? How would he advise? I paused expectantly but alas, neither a culinary scientist nor an artist had climbed from the cab. There was just me and this other guy and the other guy was at a complete loss for answers. He shrugged then shook his head slowly as if dislodged some gems that might tumble to his tounge. Alas, all he could summon was that the crop was “... bound for Europe” and as for ravioli, rye bread, pasta or pane, he had no idea. I was amazed, for had I been in his place, I would surely have followed the fate of my crop to the very mouths of its consumers. I was disappointed. So, with a limp smile and a parting weather wish, I bade him good day. Usually, I don’t pay much attention to details; they get in the way of interesting distractions. I don't read instructions before assembling IKEA furniture and recipe books stay on the shelves when I cook. A pinch of imagination and a little daring usually suffices. But this was different; a personal challenge and a small matter of honor. Specifically, could I take bare wheat from the fields and make a loaf for lunch like Bruegel's peasants? And with nothing other than “... bound for Europe”, could I create a minor culinary miracle? I needed help, so I did what any of us would do. I enrolled in Dr Google’s university for cheap and questionable advice and entered the key words “wheat, cheating and bread” then paused, considering the legitimacy of what I had done. No, no problem, as far as I was concerned, the peasants and I were now on a level playing field. They had generations of baking forefathers for guidance on and I had a laptop with high speed. Dr Google told me that I was in fact, standing in the right field for bread. It was winter wheat and winter wheat is hard and hard wheat is good for making bread. On the other hand, summer wheat is soft and good for soft things like birthday cakes, scones and muffins. “All purpose flour” is generally what one buys in the grocery store. It's a blend of both, allowing you to make softish bread and hardish muffins; a nice little factoid for intelligent-sounding dinner conversation. Let's turn our attention back to Bruegel’s painting. If you have it, notice that the peasants are cutting down the wheat with long and dangerous-looking scythes. This much maligned halloween tool is very important if you are making peasant-style bread so I am very fortunate; I have a scythe. My scythe is a thing of beauty; made of aluminium alloy, in Austria. The difference between Bruegel’s scythes and my scythe is the difference between a tricycle and the space shuttle. It is the mother of all scythes, a beautiful mesmerizing thing, swinging in sensuous arcs and slicing with wondrous efficiency. Wheat falls neatly to one side like the closing pages of a book and rows of cut heads form behind; the lines being written in that book. As romantic as this may sound, the slicing dance must end sometime or in more prosaic terms, exactly how much wheat must one cut for a single loaf of bread? I hadn’t the faintest idea. So I simply kept on scything until the clock struck twelve and my scythe turned into a pocket knife. No, not true; when there was a biggish pile of wheat, I stopped. Sunday school teaches us the biblical passage “As ye sow, so shall ye reap” and I have always found that to be useful. But what the good book fails to mention is that “..as ye reap, so shall ye thresh” then, “as ye thresh, so shall ye winnow” and ‘if ye still hath time, so shall ye grind the grains to flour”. Hopefully Biblical scholars are working on that. So, next step: “... so shall ye thresh.” No one was threshing wheat in Bruegel’s painting, unless that part of the painting is under the frame, so there were no peasants to guide me on this one. I had resolved not to grovel before Dr Google again but also knew that throwing my wheat under a passing combine was out of the question; any peasant would cry foul and importantly, I could not live with the shame. So I turned to the formal education I had received in childhood; back fifty five years, to a darkened primary school classroom, thirty fidgety kids, a shushing teacher, and a reel-to-reel black and white movie. There, jittery images revealed African women (often bare breasted!) with babies on their backs and plenty of wheat. Handfuls of wheat were being beaten (nay, threshed) repeatedly against the hard earth until the grain broke free and collected there. In my mind, I see one woman singing softly as she works, occasionally reaching back to sooth her child. With the grain gathered into in a flat basket before her, she holds it out like a tray. Then, as a line cook would do with a pancake, and with as much ease, she flips the load of wheat upward, the grain and chaff rising in a winnowing wave, with a light breeze catching the chaff. It blows away like a thousand tiny ghosts, scurrying between the huts. With each successive wave, more and more of the chaff disappears and soon, only pure grain falls back to the basket. She checks on her baby again who mercifully, sleeps peacefully. Not surprising though, for these same repetitive motions have rocked the child to sleep many times before, even before birth. Primary school had paid off. A big shallow cardboard box was recruited from the recycling bin and its defects taped up to prevent any wheat cargo from escaping. Then the threshing began. I took handfuls of wheat and beat them against the inside of the box, much as the women had done against hot, dry African earth. Releasing pent up tension from years of threshing deprivation, I beat the wheat stalks against the box and beat them again and again. Gradually this tension began to bleed away and a benign calmness descended on me. As a result of this experience, I can heartily endorse a ten to fifteen minute threshing session after a tough day at the office. And now, “... so shall ye winnow.” With my back to a breeze and the chaffy grain in the box, I tossed the mixture upward with a movie of mother, the baby and the basket of wheat playing in my head. A movie of the line cook played alongside. But the hand-eye coordination of a sixty something was no match for a twenty-something line cook or a skilled African mother. Progress was acceptable until one awkward flipping motion triggered a sudden and terrifying grain storm, heaving the load badly and causing some to skitter over the side of the box. Then a rogue wave struck and much of the precious grain breached the box wall and landed at my feet. In complete dismay, I staggered; aghast and mentally stranded on a beach of defeat. However, from adversity grows both strength and wisdom and even as the grain scattered, an embryonic stroke of brilliance was conceived. In fact, were it not for modesty, the word ‘genius’ would drop from my lips. The age of “Water winnowing” had dawned. I would throw everything into a big bucket of water and the grain would sink to the bottom. Then I would rake the soggy chaff off the surface and pour out the water to harvest the grain. Brilliant, simply brilliant! Now ask yourself why this technique was not used by the African woman; why not indeed my friend? The answer is simple. If you lived in an African village you would be soundly thrashed/threshed if you wasted water this way. You would have to walk ten miles to the river and ten miles back and a leopard could even ambush you en route. With the traditional method, wind is always on your doorstep and and while you are winnowing with the wind, buckets and water can be used more fruitfully, to make beer. Here where I live however, a water faucet is only a step away and beer, only a five minute drive down the road. So, until I find myself with a baby on my back in an African village, I will go the water route every time. It worked like a charm. I poured off the water, dried the grain in the sun for a couple of hours and confronted the final challenge ie. ‘....if ye still hath time, so shall ye grind the grains to flour”. In another time and place I would relate how the grain was poured into a stone mortar that was carved with a bronze chisel passed down from forefathers. Then, how that grain was pounded to flour using a pestle carved from a tree trunk. But, as mentioned, that would be in another time and place, perhaps even before Bruegel. Nowadays, I would simply be lying. There was no stone mortar, and not even a pestle. Like so many, ours disappeared at a yard sale in medieval times but had our ancestors been pack rats this story might have read differently. But no. So I just switched on our liquidizer and threw in the grain, hoping that such a rash thing would not end with smoke and destruction. It didn't; my extreme wholewheat flour was made. I poured warm water into a bowl with the flour, adding a little yeast and some honey to keep the yeast company. Then, with eager hands and skills gleaned from papier-mâché and kindergarten, I mixed this all together and covered the bowl to keep things moist. The dough rose with the lethargy of a lead filled balloon, then stalled but mercifully, stayed aloft at low altitude. At first I was both troubled and perplexed; concerned about my “helicopter parent” peeking or geriatric yeast or wheat that was too soft or even too hard. But slowly my naivete dawned on me. Indeed, there are none so blind as those who will not see! What lay before me was an exotic form of European flatbread; a delight I had not even dreamed of. So it was then, that one oven, three hundred and fifty degrees and thirty minutes later, this adventure into history, agriculture and sociology ended with delicious steaming, Lithuanian flatbread (prove me wrong) cooling beneath an open window. A slice, still warm, was split open and with melting butter and sweet apricot jam, fantasy became reality. Hmmm.. delicious! Take that Bruegel!

© 2016 Soutie |

Advertise Here

Want to advertise here? Get started for as little as $5

Compartment 114

Compartment 114 Stats

106 Views

Added on November 8, 2016 Last Updated on November 8, 2016 Tags: bread, wheat, Prince Edward Island, make, harvest AuthorSoutieCharlottetown, PEI, CanadaAboutA retired university teacher in the field of Veterinary Medicine more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing